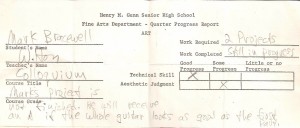

My first go at making a guitar was in high school, about 1973…

My first go at making a guitar was in high school, about 1973…

It was a bass, walnut body, mahogany neck. I ran out of money. Such is high school, I think I got a B.

Wood: I tend to keep wood around for a long time before I use it. I feel that wood that has been air dried for at least a few years is less likely to surprise with a warp, cup or bend when it’s put to work, and there’s no doubt it gets better as it ages. Hard maple neck stock I’m using now has air dried (after being kiln dried) for 4+ years, and some figured stock I have goes back 25. I’m not a slave to perfection in figure, I make instruments to be played first and looked at second (a close second), so I’ll use a blank with a streak or an odd bit of grain as long as it’s not a structural problem. It takes trees sometimes hundreds of years to make this stuff, and I don’t like to waste that hard work. I see it as character. My tastes run to maple & rosewood for necks, ebony for fretboards and mahogany, alder, linden & sugar pine for bodies but I’m always on the lookout for interesting and sustainable timbers.

Finish: Almost all my guitars are finished on the body with nitrocellulose lacquer, and on the neck with a rubbed in modified linseed oil varnish. Occasionally I’ll french polish (shellac) on an acoustic instrument. To me it’s paramount that a good instrument can be repaired. If it’s good, it should last pretty much forever, with care, so I don’t use hard to repair finishes like polyester, polyurethane or catalyzed lacquer (not to mention the air quality issues). This is also why I shy away from some of the fancy modern trends like CNC pocketed frets unless somebody asks for that.

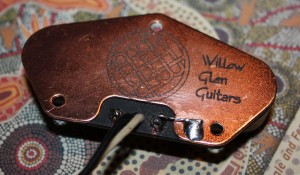

Hardware: Factory made guitars often use mass produced stamped parts that are shiny chrome but just don’t have the class that a well machined or cast & polished object can have. Luckily there are a few sources around who care about detail. I use Callaham & Pigtail bridges, Gotoh & TonePros/Kluson tuners. My truss rods are local luthier Mark Blanchard’s patented stainless steel, double action rods. A clever design with a very fine, positive adjustment, they move only longitudinally and do not twist inside the neck, allowing for a snug, rattle free installation. Spitz Design & Machine, here in Willow Glen, makes machined stainless steel covers & plates for me, as well as my steel guitar bridges. Many other parts I make myself; cast resin pickguards, bone & corian nuts, knobs & switch tips.

Hardware: Factory made guitars often use mass produced stamped parts that are shiny chrome but just don’t have the class that a well machined or cast & polished object can have. Luckily there are a few sources around who care about detail. I use Callaham & Pigtail bridges, Gotoh & TonePros/Kluson tuners. My truss rods are local luthier Mark Blanchard’s patented stainless steel, double action rods. A clever design with a very fine, positive adjustment, they move only longitudinally and do not twist inside the neck, allowing for a snug, rattle free installation. Spitz Design & Machine, here in Willow Glen, makes machined stainless steel covers & plates for me, as well as my steel guitar bridges. Many other parts I make myself; cast resin pickguards, bone & corian nuts, knobs & switch tips.

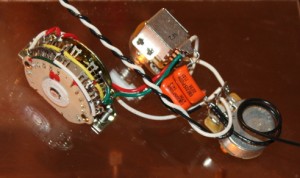

Electronics: Electric guitar wiring is a bizarre anachronism. Why phantom powered low impedance active electronics didn’t find a home in guitars will forever be a mystery to me, it’s been around since 1919 (modern 48v systems since 1966 – perhaps by then it was already too late…). But I’m OK with it, there are so many things you can do with just wire and magnets, and it’s a sound we love. I like tidy wiring that is, again, easy to repair. Sometimes vintage style wiring, if it’s that kind of guitar. I have a couple of big spools of wire manufactured in 1954, excellent tone! (That was a joke, OK?) I enjoy finding ways to get a number of different sounds with a minimum of clutter and controls. I use Lollar pickups in most guitars, they always deliver. Sometimes I wind my own T style bridge pickups for a hotter, greasier sound, and I wind most all my own lap steel pickups.

Neck Shapes: In a perfect world, I’d be able to see how a person plays before carving a neck for them. Even then, it’s a bit of luck, which is why you should play a bunch of guitars blindfolded before you pick one. I find players roughly divided into two camps, those who play with their thumb on the back of the neck and like a slimmer rounded shape, and those who play thumb-over-the-top and like a thicker more elliptical shape towards the nut. The fat, elliptical soft V is my favorite, and I tend to make those more often. Classical players probably wouldn’t like them, but street technique seems to get along pretty well. It depends on how I imagine the guitar is going to be played. You just have to try them out. Fretboards usually get a compound radius, from 9.5 or 10 at the nut to 12 at the heel.

Setup: A guitar that’s not set up well is just no fun at all. So I spend a good amount of time doing this on every guitar I make.

Tone: Well, hard to write about. I don’t have a particular sort of sound I go for. I’ll just say I’m partial to Jeff Beck, Steve Howe & David Lindley among others and we can go from there…